Marburg Virus

Marburg haemorrhagic fever is a viral disease, very similar to Ebola, caused by a virus indigenous to Africa that belongs to the Filoviridae family.

Although rare, the virus has the ability to cause epidemics with high mortality rates. In fact the virus was quickly recognised as a pathogen of extreme global importance and is currently classified as a Risk Group 4 Pathogen by the World Health Organization, and as a Select Agent by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

CAUSES

Marburg virus (MARV) is the causative etiological agent of Marburg virus disease (MVD) in humans, with a mortality rate ranging from 23 to 90%, depending on the outbreak. It is a member of the Filoviridae family, which includes the genera Marburgvirus, Ebolavirus, Cuevavirus, Striavirus and Thamnovirus.

Although generally less well known than its cousin, the Ebola virus (EBOV), MARV was the first to be discovered following outbreaks that occurred in Germany and Belgrade, in former Yugoslavia. The first cases were detected in monkey specimens imported from Uganda that infected researchers in some laboratories. A good 25 primary infections led to the death of 7 individuals.

The virus then sporadically reappeared in 1975 in South Africa and 1980 and in 1987 in Kenya, where very few cases were immediately isolated.

More serious epidemics occurred between 1998 and 2000 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in 2004 in Angola, with more than a hundred deaths.

TRANSMISSION

Transmission between humans occurs through direct contact with blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected people.

The virus is not transmitted during the incubation period, which lasts from 3 to 9 days. In fact, the time when the patient is most contagious is during the acute stage of the disease, especially during haemorrhagic manifestations. Infection is facilitated by poor sanitary conditions, frequently found in low-income countries, and where people are in direct contact with the infected person, contaminated surfaces and materials. Funeral ceremonies in which relatives and friends have direct contact with the body of the deceased also play a significant role in the transmission of the virus.

Health-care workers have been infected while treating patients with Marburg. This has occurred through close contact with patients when adequate protective nursing procedures and infection control precautions are not strictly practiced. To date, approximately 9% of Ebola or Marburg victims have been health care workers.

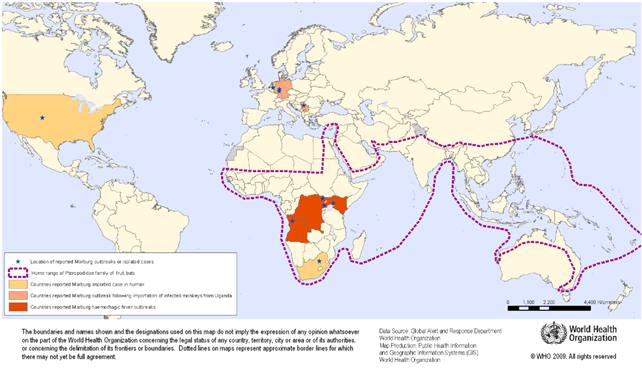

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Diseases in this group widely occur in tropical and subtropical regions. Lassa fever, Ebola, and Marburg haemorrhagic fevers occur in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1999, an outbreak was identified in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where multiple human infections are believed to have occurred in the 2 years that followed. This outbreak resulted in a total of 154 cases, with a mortality rate of 83%.

In 2005, the largest documented outbreak of MARV occurred in Angola, with 252 documented human infections and 227 deaths, with a mortality rate of 90%.

The epidemics have continued since 2005, with an outbreak recorded in Uganda in 2007, and two cases involving tourists in 2008, who were returning home from Uganda to the United States and the Netherlands. Further outbreaks have been recorded in Uganda in 2012, 2014 and 2017.

All of the recorded MARV outbreaks originated in Africa.

Several species of bats have been identified as a host reservoir for the virus, the most cited being Rousettus aegyptiacus, the Egyptian fruit bat.

Numerous cases have been reported among tourists and miners, who most likely contracted MARV in the caves inhabited by these animals.

The live virus was isolated from R. aegyptiacus bats inside the Kitaka Mine in Uganda, the place where the miners diagnosed with MVD had worked.

SYMPTOMS

Due to the rural nature of most of the outbreaks in Africa, there are few detailed clinical descriptions of MVD. Consequently, the availability of pathological and laboratory data is limited.

The most detailed descriptions come from the initial outbreak in Marburg, Germany, and Johannesburg, in South Africa, which involved three patients and a few isolated cases.

Like many other infectious diseases, MVD cases initially report flu-like symptoms, such as chills, fever, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, joint pain, and malaise, which emerge between 2 to 21 days after the initial infection.

Within 2-5 days of the first symptoms, patients may experience abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhea, and lethargy.

On days 5-7, the intensity of the disease increases and may present with a maculopapular rash that spreads from the trunk to the limbs, conjunctivitis, sustained fever, and symptoms of haemorrhagic fever, such as mucosal bleeding, petechiae, blood in stool, vomiting, and bleeding from venipuncture sites.

The maculopapular rash starts as small, dark red spots around the hair follicles on the torso and sometimes on the upper arms, developing into a diffuse rash, which can become a dark erythema that covers the face, neck, chest, and arms.

Neurological symptoms, such as confusion, agitation, increased sensitivity, seizures, and coma may occur in the later stages of the disease.

Patients either recover from the disease or die from dehydration, internal bleeding, organ failure, or some combination of systemic factors facilitated by a dysregulated immune response to the virus. Patients who survive do not normally experience the severe symptoms of the advanced stage of the disease, but may experience sequelae, such as arthritis, conjunctivitis, myalgia, and symptoms of psychosis, during and after recovery.

DIAGNOSIS

Marburg virus infection should be suspected in patients with a predisposition to bleeding, fever, and other symptoms, in accordance with the previous filovirus infections, on return from travel to endemic areas.

Tests useful in identifying the disease include complete CBC, routine blood tests, liver function tests, coagulation tests, and urinalysis.

Diagnostic tests include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and RT-PCR (Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction). The standard method for diagnosis is identification of the characteristic virions by means of electron microscopy of infected tissue or on blood.

TREATMENT

There is no specific treatments for Marburg. The only available treatment is supportive care to assist the patient, when possible, by attempting to restore the patient’s fluid and electrolyte levels, provide oxygen and blood transfusions.

Several promising candidate drugs are underdevelopment, but their safety and efficacy in humans is not yet known.

PREVENTION

There are no licensed vaccines or treatments for MVD. This is partly due to the difficulty in performing clinical trials, due to the severity, infrequency and rural nature of MVD outbreaks.

People travelling to a country with a Marburg outbreak are advised to gather information about the disease before departure so they can seek immediate medical attention at the first signs of fever; adopt stringent hygiene practices (such as washing hands frequently), and avoid eating bushmeat, such as chimpanzee or monkey meat.

Bibliography:

- Pierce Reynolds, Andrea Marzi. Ebola and Marburg virus vaccines. Virus Genes (2017) 53:501–515 DOI 10.1007/s11262-017-1455-x.

- Kyle Shifflett and Andrea Marzi. Marburg virus pathogenesis – differences and similarities in humans and animal models. Shifflett and Marzi Virology Journal (2019) 16:165

- Saranya A. Selvaraj Karen E. Lee, Mason Harrell, Ivan Ivanov, and Benedetta Allegranzi. Infection Rates and Risk Factors for Infection Among. Health Workers During Ebola and Marburg Virus Outbreaks: A Systematic Review. Health Workers and EVD/MVD Outbreaks • JID 2018:218 (Suppl 5) • S679;

World Health Organization 2014. Ebola Strategy. Ebola and Marburg virus disease epidemics: preparedness, alert, control and evaluation. Annex 36. WHO International Health Regulations (IHR).