Lassa fever

Discovered in 1969 in Nigeria, Lassa fever is a viral disease that causes a life-threatening form of haemorrhagic fever. Found in several West African countries, cases have been reported following travel to endemic regions, but also in several other countries, such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Israel, Sweden, and Germany.

CAUSES

Lassa Fever virus is a single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus that belongs to the Arenaviridae family of viruses.

An important feature is the high genetic variability of some strains of the virus, which are capable of evolving and changing over time. This variability is an important element for the design of diagnostic tools and the development of a universal vaccine that can be used in different geographical settings, regardless of the strain in circulation. Different strains also influence the types of symptoms and the severity of the infection.

The animal reservoir for LASV is typically the “multimammate rat" (Mastomys natalensis), a rodent of the genus Mastomys ubiquitous in West Africa. The infection affects the uterus of rodents, which remain affected for the rest of their lives. These rats do not get ill, but continue to release the virus in their urine and faeces.

Although M. natalensis is considered the natural reservoir of LASV, there are also other rodent reservoirs (Mastomys erythroleucus and Hylomyscus pamfi), which recent discoveries have also identified as being involved in the spread of Lassa fever.

TRANSMISSION

Transmission mainly occurs through direct or indirect contact with infected rodents. During the dry season, Mastomys rodents invade inhabited houses in search of food, which exposes humans to LSAV infection through contact with urine, faeces, blood or meat of infected Mastomys rodents. Infection is thought to occur via direct inoculation of mucous membranes or inhalation of aerosols produced when rodents urinate or defecate. The frequency of infection related to these modes of transmission remains unknown.

Person-to-person transmission usually occurs among individuals living in overcrowded housing situations, in care setting for sick people, or individuals involved in burial practices. LASV can also be transmitted through direct contact with blood, urine, faeces or other bodily secretions of infected individuals or even through accidental contact with contaminated needles and medical equipment.

Cases of sexual transmission occurring months after recovery from acute disease have been reported.

Lassa fever can affect all age groups and both genders. For reasons still unknown, in paediatric subjects, the disease is more common among male children.

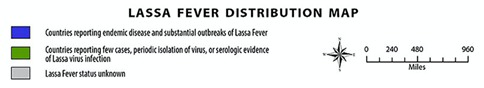

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

As mentioned previously, Lassa fever is endemic in West Africa, with cases reported in Nigeria, Benin, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and Ghana.

The epidemiology of the virus is complex because a large proportion of cases are asymptomatic, surveillance systems are not very affective, and specific diagnostic tests for Lassa fever are often lacking.

Cases of Lassa fever, associated with travel outside West Africa to the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Israel, and Germany, have been documented among aid workers, missionaries, and foreign military personnel

SYMPTOMS

The incubation period of Lassa fever ranges from 2 to 21 days. Symptoms are usually mild (an element that complicates diagnosis), with a gradual onset characterised by nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, general weakness, malaise, and headache.

After a few days, symptoms become more acute and are followed by sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, arthralgia, abdominal and back pain.

Up to one-fifth of infected individuals experience more severe symptoms, such as facial swelling, bruising, respiratory distress, hepatitis, renal failure, convulsions, tremors, gait disturbance, disorientation, loss of consciousness, and bleeding from the mucous membrane of the mouth, nose, vagina, or gastrointestinal tract. Bleeding is a symptom reported by 30% of patients with Lassa fever.

Finally, the more severe cases of LASV present excessive clotting, pleural or pericardial effusion (accumulation of fluid around the lungs or heart), miscarriage, renal failure, multiorgan failure, hypovolemic shock (sudden reduction in circulating blood volume) similar to sepsis, headache, and bilateral or unilateral deafness.

The mortality rate is approximately 30% in children, with generalised edema, abdominal distension and bleeding. Genetic and immunological studies are underway to better understand the evolution of the disease and the defensive mechanisms underlying Lassa fever.

Lassa fever during pregnancy can cause severe illness, high maternal mortality rates in the third trimester, and miscarriage, with an estimated foetal mortality rate of 95%.

DIAGNOSIS

Early identification of patients with Lassa fever is critical to maximise the benefits of available antiviral therapies and the implementation of appropriate infection control measures.

The nonspecific symptoms of Lassa fever make it difficult to distinguish it from other common endemic microbial diseases, such as malaria, shigellosis, typhoid fever, and other viral haemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola and yellow fever, which are both endemic to West Africa.

A range of diagnostic tests are available, including cell culture, immunofluorescence assays, complement fixation assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for LASV antigens and IgM antibodies, polymerase chain reaction with different assays and targets, lateral flow tests and other rapid tests.

Currently, molecular biology tests are mainly used for diagnosis, amplifying nucleic acid extracted from biological samples by means of traditional or Real-Time RT-PCR.

TREATMENT

Supportive therapy is essential; adequate fluid intake and electrolyte balance, good oxygenation and blood pressure control must be maintained. Sometimes dialysis to maintain renal function is required. Secondary bacterial infections should be treated with antibiotics.

Targeted antiviral therapy with the antiviral agent ribavirin can improve the treatment outcome if administered during the early stages of the disease. However, although ribavirin has been widely used for treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis, treatment of Lassa fever with ribavirin is still being studied.

More recent therapies include favipiravir, a broad-spectrum RNA inhibitor against RNA viruses, which has been shown to reduce LASV viremia in animal studies.

PREVENTION

In areas at risk, contact with Mastomys rodents should be avoided to reduce the risk of LASV transmission to humans. In these cases, measures should be taken to avoid infection, include storing foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, keeping the house and surrounding areas clean, keeping rodent populations down, and avoiding contact with droppings or urine.

In health care settings, strict adherence to standard infection prevention and control precautions is essential to prevent the spread of human LSAV infection, particularly when treating patients with fever of undetermined origin and suspected viral haemorrhagic fevers in endemic areas. Such measures include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment and safe injection practices.

There are currently no effective vaccines for Lassa fever, but there are several under development, including LASSARAB and an inactivated recombinant LASV. The recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) vaccine that expresses LASV glycoprotein (VSV-LASV-GPC) is among the primary candidates developed so far and has been targeted for accelerated development by The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations Foundation, which is supporting the development of Lassa vaccine candidates.

Bibliografia:

- Aaron Kofman, Mary J. Choi, Pierre E. Rollin. Lassa Fever in Travelers from West Africa, 1969–2016. Emerging Infectious Diseases. Vol. 25, No. 2, February 2019.

- Danny A. Asogun, Stephan Günther, George O. Akpede, Chikwe Ihekweazu, Alimuddin Zumla. Lassa Fever. Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Management and Prevention. Infect Dis Clin N Am 33 (2019) 933–951.

- Jyothi Purushothama,b, Teresa Lambea, Sarah C. Gilbert. Vaccine platforms for the prevention of Lassa fever. Immunology Letters 215 (2019) 1–11

- Anise N. Happi1, Christian T. Happi2,3, Randal J. Schoepp. Lassa Fever Diagnostics: Past, Present, and Future. Curr Opin Virol. 2019 August ; 37: 132–138.