Rabies

Rabies is a highly fatal zoonotic disease caused by the rabies virus. It mainly affects animals but can occasionally affect humans, usually as a result of a bite from an infected animal.

Animals, particularly wild animals, are the main reservoir of the infection. In northern and central Europe, the fox, badger and other mustelids play a significant roles, as they maintain the disease in an endemic state. In other countries, small rodents, such as squirrels, mice, rats (southern Europe) and bats (America), are also a significant source of infection.

CAUSES

The etiological agent of rabies is a virus that belongs to the Lyssavirus genus of the Rhabdoviridae family. The virion has a helical symmetry and a ribonucleoprotein core that contains RNA encased within a surrounding envelope, with filamentous growths that can stimulate the synthesis of neutralising antibodies and inhibit hemagglutination (the aggregation of red blood cells).

The nucleocapsid contains RNA, and its complex antigenic structure affects production of specific antibodies. Neutralising antibodies are protective. Rabies virus has a relatively low resistance. Although stable at low temperatures, it caǹ be inactivated by heat, UV light, sunlight and formalin.

TRANSMISSION

Rabies transmission can occur when the saliva of an infected animal comes into direct contact with human mucosa or fresh skin wounds, which is usually caused by a bite or scratch. Virus replication occurs from the point of inoculation (where the virus entered the body), starting from within the striated muscle fibrocells.

The virus spreads by travelling along the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system, where it multiplies and continues to the salivary glands.

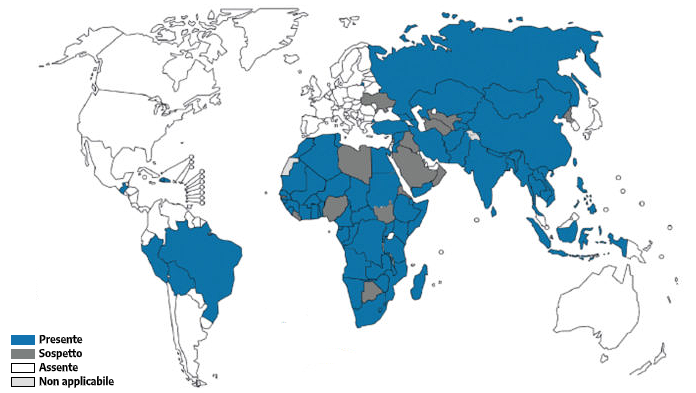

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Rabies is a neglected but preventable tropical disease, with a mortality rate of almost 100%. It is widespread throughout the world, with an annual death rate of approximately 59,000 cases. Asia and Africa have a higher prevalence of rabies than other continents. In these regions, 40% of cases occur in children under 15 years of age. The mortality rate among travellers is much lower.

It is important not to regard rabies as a disease of the past, but as a pathological situation that we still need to deal with today.

Europe has achieved rabies-free status in many areas, but the rabies vaccine for pets or companion animals remains important for animal health and the prevention of outbreaks.

Approximately 80% of cases are caused by wild species of animals. In this respect, the most dangerous species is the red fox. About 30 years ago, a form of oral anti-rabies for foxes was developed in support of the theory that eliminating infection in wild species leads to the elimination of rabies in domestic animals. This theory has led to incredible results. In fact, while 21,000 cases of rabies were reported in Europe in 1990, these figures dropped to 5,400 in 2004

Eradication occured in Italy from 1997 to 2008. Subsequently, however, the Istituto zooprofilattico sperimentale delle Venezie (IZSVe), a Venetian research institute for the prevention and monitoring of zoonotic diseases, released data showing hundreds of positive cases in the Veneto, Trentino Alto-Adige, and Friuli Venezia-Giulia regions between 2008 and 2010. The situation has been linked to the sylvatic rabies outbreak in Slovenia. However, the affected regions have taken due precautions and managed to decrease the number of infections over time.

SYMPTOMS

The typical incubation period is 1-2 months, but can be highly variable. The clinical manifestations of rabies can be distinguished into three sequential stages, which occur after an incubation period that varies on average from 1 week to 3 months, but in some cases more than 1 year.

Latency can depend on several factors: the viral load, the extent of the wound, the immune system of the infected person, and how far away the wound is from the central nervous system.

Generally, the incubation period is quite long, ranging from 20 to 90 days.

Rabies can manifest in two forms:

The furious form, which makes up about 75% of cases, can be divided into three stages:

- Nonspecific prodromal syndrome (schizophrenia-type symptoms) that can last for 1 to 4 days. During this stage there may also be a variety of different symptoms, such as fever, migraine, general malaise, nausea, vomiting, sore throat, non-productive cough, and myalgia. 50-80% of patients experience a loss of sensation or involuntary muscle contractions (fasciculation) in the area of initial exposure site.

- Acute encephalitic stage, preceded by periods of motor hyperactivity and agitation, followed rapidly by symptoms of confusion, aggression, hallucinations, muscle spasms, convulsions, and paralysis. In this stage, the patient alternates between moments of delirium and lucidity, which, however, become increasingly rare until the patient eventually falls into coma. Hyperesthesia with excessive sensitivity to bright light, loud noises, and touch, is also very common. Paralysis of the vocal cords is common, and body temperatures can reach 40°C.

- The encephalitic stage causes severe alterations to the brainstem. This can causes problems with vision, such as optic nerve inflammation or double vision, facial paralysis, and difficulty swallowing, a typical symptom of the disease. At this stage, 50% of cases suffer hydrophobia with difficulty breathing, with violent and painful contractions of the respiratory muscles, due to the over-production and ingestion of salivary fluids, which eventually leads to a comatose state.

The paralytic form (approx. 25% of cases) is characterised by increasing paralysis. It is common in individuals who have been bitten by a bat and people undergoing treatment after exposure to the virus. In Southeast Asia it occurs in people who have been bitten by infected dogs.

The lethality rate for rabies virus is still very high if not treated promptly. In most cases, death occurs 2 to 10 days after the initial onset of symptoms. Once symptoms begin, survival is extremely rare; in fact, the mortality rate for this clinical profile is approximately 99%.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical diagnosis maỳ be difficult in the prodromal stage; encephalitic symptoms must be differentiated from poliomyelitis and other viral neuraxitis (inflammation of the nervous system), whereas tetanus is easily distinguished by lockjaw and opisthotonos (contractures and stiffness of muscles), which are always absent in rabies. Diagnostic confirmation is based on isolating the virus in saliva, CSF, urine, and nasal and conjunctival secretions.

Serological diagnosis uses titration of neutralising and complement-fixing antibodies: these appear either during natural infection or following vaccination, but at a higher titer in the former case. Direct microscopic examination of autopsy material allows for microscopic detection of Negri bodies in brain tissue and identification of the virus using the direct immunofluorescence method.

TREATMENT

There are no effective drug therapies for rabies infection; medical literature shows very few patients have survived the disease, which was also due to the type of intensive medical care they received. Consequently, a number of prophylactic measures must be carried out following exposure to the virus, such as cleaning the wound thoroughly, and treatment with immunoglobulin and vaccination are essential.

There is no time limit for the administration of immunoglobulin. Most should be administered deeply into in the wound. WHO recommends keeping the suspected animal under observation for about 10 days, as symptoms for pets, such as dogs and cats, are not very specific. In other nations such as France, England and Spain, the recommended observation period is approximately 14 days.

PREVENTION

Education of children by parents, teachers and paediatricians on the importance of avoiding contact with stray or wild animals is also a measure of primary importance. Children should be warned not to tease or attempt to capture animals they might encounter, especially during a journey abroad.

The most widely used rabies prophylaxis measure in industrialised countries is the vaccination of domestic animals and the capture and vaccination of wild animals.

WHO guidelines have indicated three principal types of exposure that should be avoided:

- Direct skin contact (even when skin is intact), with animals, their mucous membranes, or their food.

- Minor scratches, grazes without bleeding, animal licks on wounds, or small bites on already grazed/broken skin (rabies vaccination is recommended in these cases).

- Single-bite, multiple bites, scratches, contamination of the mucous membrane with saliva, or suspected contact with bats.

Pre-exposure vaccination (PrEP)

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with the rabies vaccine is an important part of rabies prevention, but it is only used exceptionally. Although administered long before exposure, PrEP simplifies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) because immunoglobulins are no longer needed and only 2 vaccinations are required instead of 4.

The new, 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend PrEP with rabies vaccine for people at high risk of rabies exposure due to their occupation or travel in an endemic environment that has limited access to timely and appropriate PEP.

Current WHO-recommended PrEP schedules are two doses of vaccine administered on days 0 and 7.

Recommendations on rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for travellers have long been based on data from populations living in endemic areas. This has led to the preferential recommendation of rabies vaccination for children or long-term travellers, assuming that the risk of exposure is related to the length of stay in the rabies endemic area.

Recent data have shown that the protection conferred by a primary course of vaccine is long-term. Preventive vaccination against rabies should therefore be considered a long-term investment and widely applicable to travellers.

In case of suspected exposure:

The prophylactic measures to be taken in case of a suspected animal bite are as follows:

- Immediate cleansing of the wound with abundant soap and water to reduce viral load, followed by application of 40- to 70% ethyl alcohol; suturing should be postponed; in the case of deep wounds, anti-rabies inoculation and possibly tetanus prophylaxis is recomended;

- immunoprophylactic treatment of the animal (if definitely infected), or in the case of deep or localized head and neck wounds. Prophylaxis should be carried out as early as possible; in this case, it is known as post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure vaccination (PEP)

Indications for post-exposure prophylaxis (following potential risk of rabies) depend on the type of contact with the rabid animal. The World Health Organization (WHO) distinguishes the type of prophylaxis, based on the type of risk or exposure. Assessment is variable depending on the patient's medical history, as well as the geographical risk and extent of injury.

The new post-exposure treatments are administered in schedules of 4 or 5 doses, depending on the above mentioned variables.

Bibliography

Damanet B., Costescu D.I., Soentjens P. Factors influencing the immune response after a double-dose 2-visit pre- exposure rabies intradermal vaccination schedule: A retrospective study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. El Sevier 33(2020) 101554

Gautret P, Schlagenhauf P, Fischer P R, One-week, two-visit, double-dose, intra-dermalrabies vaccination schedule for travelers: T Time/dose sparing, effective but “off label”. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 33 (2020) 101563

Moroni M., Spinello A., Vullo V. Manuale di Malattie Infettive. Edra LSWR, Masson, 2014.

Bartolozzi G. Vaccini e Vaccinazioni, Seconda Edizione. Masson 2015.

Rugarli C., Obiass M., Medicina interna Sistematica, Quinta Edizione. Masson 2015; 1585-1586