Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the HCV RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family. The disease primarily affects the liver, where it initiates a process that can degenerate into chronic Hepatitis C in 50-80% of patients.

Since the discovery of the virus in 1989, intensive traditional, translational, and clinical research has led to constant advances in the development of diagnostic tools and management strategies. Advancements that have been critical in treating what is one of the most serious forms of liver disease, and the leading cause of liver transplant.

CAUSES

HCV is a virus of the Flaviviridae family which belongs to the genus Hepacivirus. HCV virions are 45-65 nm in diameter with E1 and E2 glycoproteins embedded in the lipid bilayer.

HCV is a very heterogeneous virus. Phylogenetic analyses of HCV strains isolated in various regions of the world have led to the identification of seven major HCV genotypes, designated 1-7. HCV genotypes include a large number of subtypes, identified by lowercase letters (e.g., 1a, 1b, and so on).

The genotype influences the course of the disease and response to antiviral therapy.

TRANSMISSION

HCV is most commonly transmitted through exposure to infected blood, caused by reuse or inadequate sterilisation of medical equipment or reuse and sharing of contaminated syringes or needles in drug users.

The latter accounts for 50-60% of the current acute HCV infections in Europe and the United States.

In the past, inadequate health care facilities led to a high incidence of cases. Needle injuries among health care workers, cases of patient-to-patient transmission or unregulated spread during tattoo sessions still occur. However, none of the listed risk factors can be identified in a considerable number (up to 40 percent in the Western world) of HCV-infected patients.

Equally, mother-to-infant and sexual transmission still occur, but are less common than in the past. However, it is often seen in the case of unprotected homosexual intercourse between HIV-infected men.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

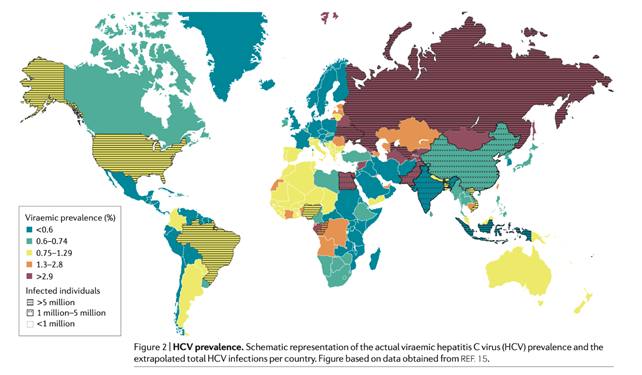

The global prevalence of HCV-infected individuals, i.e. patients with positive HCV antibodies, is estimated at 1.6%, which corresponds to approximately 115 million individuals. However, this figure also comprises individuals who have cleared the virus spontaneously or as a result of treatment. Consequently, the global number of currently positive cases is lower and estimated at 1%, or 71 million HCV-infected individuals.

These estimates are based on extrapolations from 100 countries where generalisable studies have been conducted. The availability of robust global data is unfortunately limited: only 29% of low-income countries and 60% of high-income countries report HCV prevalence. In addition, the quality of the reported data varies from country to country.

The prevalence of HCV infection shows considerable variations across the globe, with the highest rate is found in countries with a past or present history of iatrogenic infection (i.e., infections caused by a physician or medical therapy).

The adult populations of Cameroon, Egypt, Gabon, Georgia, Mongolia, Nigeria, and Uzbekistan have an anti-HCV antibody prevalence >5%; iatrogenic infection is a key risk factor in these countries.

The major cause of HCV infection in Egypt is well documented and attributed to intravenous treatment of schistosomiasis during the 1960s-1970s.

Western countries account for only a small percentage of global HCV infections. China, Pakistan, India, Egypt and Russia account for half of the total HCV2 viral infections combined.

In specific areas, the age of HCV patients correlates with the primary source of infection. In countries where injected drug use is a significant ongoing risk factor (e.g., Australia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Russia, and the United Kingdom), the peak age of the HCV-infected population is approx. 30 years. Whereas, the peak age rises (50-60 years) in countries with a prevalence of iatrogenic infections.

This difference is explained by the fact that active recreational drug users are generally young, whereas most iatrogenic infections occurred prior to the 1990s, before HCV diagnostics became available.

Some countries have a mixed age profile caused by the presence of several different risk factors.

HCV genotype distribution also varies by region, which has implications in the clinical course of the disease, the treatment requirements and drug development.

SYMPTOMS

In most cases, acute infection occurs without symptoms and no clinical signs of disease.

A minority of patients develop acute hepatitis C, with jaundice, fatigue, pain or discomfort in the right upper abdomen, or arthralgia (joint pain).

Acute HCV infection leads to chronic infection in about 75-85% of people; over the next 20-30 years, a proportion of patients will progress to cirrhosis and other cirrhosis-related sequelae, such as decompensated liver and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Before developing decompensation symptoms, patients may experience symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, muscle and joint pain, or discomfort, pain, or itching in the right upper abdomen.

Progression is not necessarily a linear process and can be accelerated by numerous factors, including the patient's age, gender, alcohol consumption, and co-infection with other viruses, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HIV, or other infectious agents such as schistosomiasis.

Finally, many patients with chronic HCV infection remain asymptomatic for years and become aware of this life-threatening disease only after they have already developed cirrhosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Several virological tools can be used to diagnose and monitor HCV infection.

Today, diagnosis of hepatitis C is based on the use of two blood tests: the detection of specific antibodies to the infection and HCV-RNA testing to detect viral particles. These tests are sensitive and specific, can be fully automated, and are relatively inexpensive.

The serological window between infection and seroconversion, i.e. when the anti-HCV antibodies become detectable, varies on average between 2 to 8 weeks. Consequently, testing solely for anti-HCV antibodies may not be useful to detect early-stage infection.

Once the presence of the virus has been established, further investigations can be performed to accurately define the impact of the disease on the liver, such as liver biopsy or other indirect methods.

Anti-HCV antibodies are detected in patients who go on to develop chronic infection and can last for years or even decades in people who clear the virus.

Rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of HCV antibodies are increasingly used for screening in low-to-moderate risk populations. In fact, it is a critical diagnostic tool, both in preventing transmission and improving the health of people with an active infection.

An estimated 45 to 85 percent of infected people are unaware of their condition because Hepatitis C usually has no symptoms until the later stages of the disease.

HCV testing is recommended in specific populations, which should be based on HCV prevalence, proven benefits of treatment (i.e., signs of disease progression and/or impaired liver function) and treatment in reducing the risk of HCC and all-cause mortality.

In most countries, hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing is recommended for the following groups at increased risk:

- Current or previous drug addicts;

- In people who received coagulation factor concentrates before 1990;

- Transfusion recipients, who received blood from donors who later tested positive for HCV, and recipients of blood, blood components, or organ transplants before the 1990s;

- Patients currently or previously on long-term haemodialysis, with persistently abnormal levels of alanine aminotransferase (a marker of liver function);

- Individuals who have undergone past invasive medical procedures, such as surgery and endoscopic procedures;

- Individuals with HIV infection;

- Health care and public safety workers at risk of needle-stick accidents, stab wounds, or general exposure to HCV-positive mucous and blood;

- Children born to HCV-positive women;

- Individuals with multiple sexual partners;

- Birth cohort screening, for example, in the United States (individuals born between 1945 and 1965).

TREATMENT

Acute Infection

Recommendations for treatment of acute hepatitis C are still under discussion and will be influenced by ongoing and future studies.

Only patients with confirmed HCV infection, i.e., after serum detection of HCV RNA, should be given antiviral therapy.

There are no indications for prophylactic treatment of hepatitis C (e.g., in health care workers after a needle-stick injury).

Individuals with acute HCV infection, with increased levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin (patients with jaundice, the so-called symptomatic acute hepatitis C), are more likely to recover spontaneously, but treatment response rates are similar.

Chronic Infection

The development of DAAs (Direct-acting Antiviral Agents) has revolutionised treatment of chronic HCV infection.

In recent years, research has shed light on the HCV life cycle, which has led to the development of drugs that target the three proteins involved in the crucial stages of its existence. A combination of one to three of these different drugs leads to cure rates of 90-100%.

Due to rapidly developing research and the approval of new drugs every few months, recommendations for HCV treatment by national and international scientific societies have been updated regularly over the past five years.

All patients with chronic hepatitis C and detectable HCV RNA in serum should be considered for antiviral treatment. However, before starting treatment, other causes of the liver disease should be ruled out. The stage of the disease must also be considered and treatment must be followed up with an evaluation of the biochemical activity of the disease.

PREVENTION

There are no vaccines available to prevent HCV infection.

Primary prevention is necessary to reduce viral load and the possibility of contracting the related diseases. These actions are aimed at reducing or eliminating HCV transmission through infected blood, blood components and plasma-derived products; high-risk activities, such as unsafe injection drug use and unprotected sex with multiple partners; and exposure to blood in health care facilities and other locations (e.g., tattoo and piercing studios).

Secondary prevention activities can reduce the risk of chronic disease by identifying HCV-infected individuals by means of appropriate screening, medical management and antiviral therapy.

One of the main problems in preventing HCV infections is that the disease does not immediately cause symptoms, which means many individuals are unaware they are infected. Identifying the vast number of people who unknowingly suffer from the chronic form of the disease should be one of the main objectives of current prevention programmes.