Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an infectious viral disease, caused by the HAV virus of the genus Hepatovirus.

Unlike hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A does not cause chronic liver disease and is rarely fatal. However, it can be debilitating and, in more severe cases, can cause fulminant hepatitis (acute liver failure), which is often fatal.

CAUSES

The Hepatitis A virus (HAV), is a nonenveloped RNA virus classified as picornavirus. The virus was first isolated in 1979. Humans are its only natural host, although several nonhuman primates have been infected under laboratory conditions.

TRANSMISSION

HAV is spread orally (via faecal-oral transmission), when an uninfected person ingests food or water contaminated with the faeces of an infected person. The virus then starts to replicate in the liver. Although rare, waterborne outbreaks are usually associated with contaminated or inadequately treated water.

After 10-12 days, the virus enters the blood and is excreted via the biliary system into the faeces. Peak titers occur during the two weeks before onset of the disease. Although the virus is present in serum, its concentration is several orders of magnitude lower than in faeces. Most infected persons no longer excrete virus in the faeces by the third week of illness. Children can excrete the virus longer than adults.

The virus can also be transmitted through close physical contact (such as oral-anal sex) with an infectious person. Casual contact among people does not spread the virus.

Transmission also occurs indirectly: in fact, there have been many cases of transmission through ingestion of contaminated food or water, particularly raw food, such as shellfish.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Overall, WHO estimates that in 2016, 7,134 people died of hepatitis worldwide (accounting for 0.5% of mortality due to viral hepatitis).

Hepatitis A is widespread across the globe. In some countries, poor sanitation, badly functioning sewage systems, and difficult access to potable water, are among the main causes of infection. In recent years, there has been an increase in symptomatic transmission of the virus in Western countries and industrialised areas.

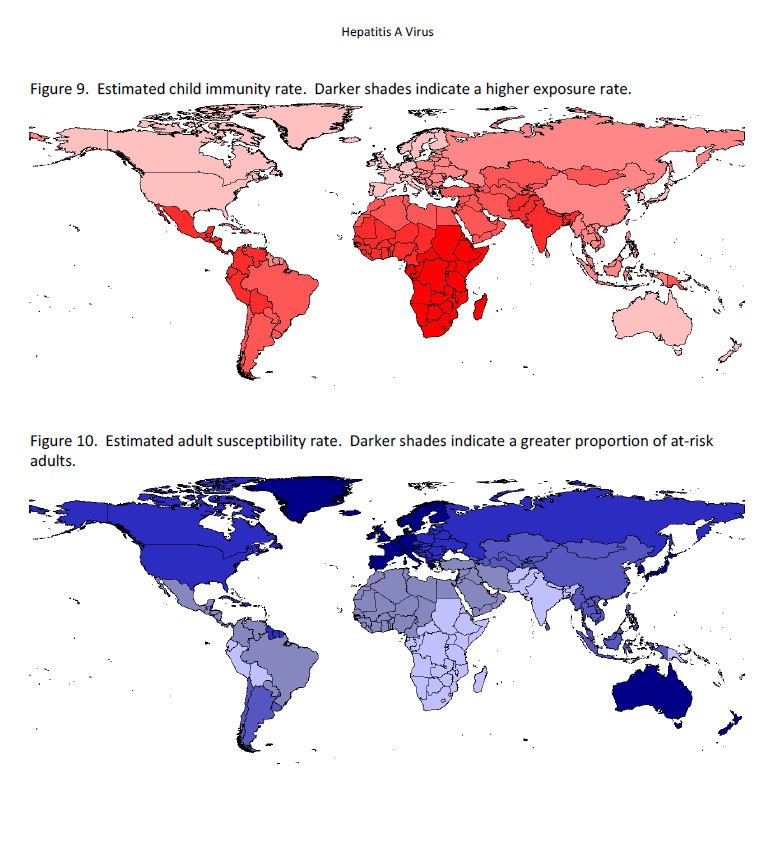

HAV is common in areas with inadequate sanitation and limited access to clean water. In highly endemic areas (such as parts of Africa and Asia), a large proportion of adults in the population are immune to HAV, and outbreaks of hepatitis A are rare. Childhood transmission is less frequent in areas of intermediate endemicity (such as Central and South America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia), whereas adolescents and adults are more susceptible to infection, making epidemics more likely. Infection is far less common in areas of low endemicity (such as the United States and Western Europe), but the disease still occurs among people in high-risk groups, travellers, and localised, community-level outbreaks.

Hepatitis A is one of the most common, vaccine-preventable infections acquired during travel. Travel-related cases of hepatitis A may occur more in people who live in or visit rural areas, or frequently eat or drink in overcrowded environments with poor hygiene conditions, such as large capital cities.

SYMPTOMS

The incubation period for hepatitis A is approximately 28 days, but can vary between 15 and 50 days.

Cases of hepatitis A are not clinically distinguishable from other types of acute viral hepatitis. The illness typically has an abrupt onset of fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, abdominal discomfort, dark urine, and jaundice. Clinical illness usually lasts no-15% longer than 2 months, although 10% to 15% of patients show prolonged or relapsing signs and symptoms for up to 6 months.

The virus can be excreted during relapse. The likelihood of symptomatic illness from HAV infection is directly related to age. In children under 6 years of age, most infections (70%) are asymptomatic. In older children and adults, the infection is usually symptomatic, with jaundice occurring in more than 70% of patients.

Severe clinical manifestations of hepatitis A infection are rare; however, atypical complications may occur, including immunologic, neurologic, hematologic, pancreatic, and renal manifestations. Relapsing hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis A, hepatitis A triggering autoimmune hepatitis, subfulminant hepatitis, and fulminant hepatitis have also been reported. Fulminant hepatitis is the most serious rare complication, with mortality estimates of up to 80%. In the pre-vaccine era, fulminant hepatitis A caused about 100 deaths per year in the United States. Overall case-fatality rates are estimated at approximately 0.3% for all ages, but may have been higher among older people (approx. 2% among adults aged 40 or older). The most recent case fatality estimates range from 0.3% -0.6% for all ages and up to 1.8% among adults aged 50 years or older.

Vaccination of high-risk groups and other public health measures have significantly reduced the number of overall hepatitis A and fulminant HAV cases. However, hepatitis A causes substantial morbidity.

DIAGNOSIS

Blood tests for HAV-specific immunoglobulin G (IgM) antibodies or PCR tests to detect viral RNA are required to confirm diagnosis of Hepatitis A infection.

TREATMENT

There is no specific treatment for hepatitis A. Recovery from symptoms after infection can be slow and may take several weeks.

Medical management is aimed at supporting clinical well-being, including replacement of fluids lost due to vomiting and diarrhoea. Consequently, treatment and management of symptoms are supportive.

PREVENTION

To counter the global spread of the hepatitis A virus and possible contagion, vaccination is the safest way forward. The vaccine can be administered to both adults and children.

Anyone who frequently travels for any purpose or duration to countries with a high or intermediate HAV endemicity should be vaccinated. Many medical experts in International and Travel Medicine believe that all travellers should be educated about the risks of hepatitis A and be offered the opportunity to get vaccinated.

In addition to vaccination, dietary behaviour can also help reduce the risk of HAV infection, along with correct hand washing before handling food. Improved sanitation, food safety, and immunisation are the most effective cornerstones for combating hepatitis A infection.

Raw food

Raw food should be avoided as much as possible. Raw fruits or vegetables are safer if you can peel them yourself or wash them in clean, safe (bottled or disinfected) water. Avoid any dishes with pre-chopped fruit or vegetables, such as salad and fruit salads. Also, avoid fresh sauces or other condiments made from raw fruits or vegetables. Raw meat or seafood are at a high risk of contamination.

Street food

The same food rules apply to street food. In this case opt for foods cooked on the spot.

Tap water

In poorer countries, it is probably advisable not to drink the tap water, even in cities. This includes ingesting water while showering or brushing teeth. In some areas it is advisable to brush teeth with bottled water. Tap water can be disinfected by boiling, filtering or chemically treating it, e.g. using specific chlorine products. Ice cubes, which are probably made with the local tap water, should also be avoided.

Freshly squeezed juice

If you have washed the fruit in potable water and squeezed the juice yourself, it can be considered safe. Juice squeezed by a stranger could be risky. The same goes for ice lollies and other foods made from freshly squeezed juice.

A key recommendation for all travellers to at-risk areas is to avoid consumption of raw food and drinks that contain ice or unpasteurised milk.

Source:

epicentro.iss.it/epatite/epatite-a

cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/index.htm