Cholera

Cholera first emerged in the 19th century and spread across the globe due to the Industrial Revolution, which caused a sudden increase in population growth and a rise in international travel. The disease has caused millions of deaths and seven pandemics, since 1817 (when it first spread from India), the latest of which is still ongoing.

CAUSES

Cholera is an infectious disease caused by the toxins released by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Of the over 200 serotypes of this vibrio that exist in the world, two serogroups in particular are involved in human epidemics: O1, the most common, and O139, found in some parts of Asia.

Upon entering the body, the bacteria travels to the intestinal lumen, where it produces a toxin that penetrates the surrounding cells, damaging their ability to absorb fluids.

TRANSMISSION

Transmission occurs via the faecal-oral route, via direct or indirect contamination of food and water by the faeces of infected humans. The main vector is contaminated water, which can be ingested directly or transmit the bacterium to other vectors, e.g. when used to wash food or utensils. However, transmission can also occur in more subtle ways, as in the case of fruits and vegetables contaminated by irrigation, or fish and seafood that have come into contact with the vibrio in the sea or waterways.

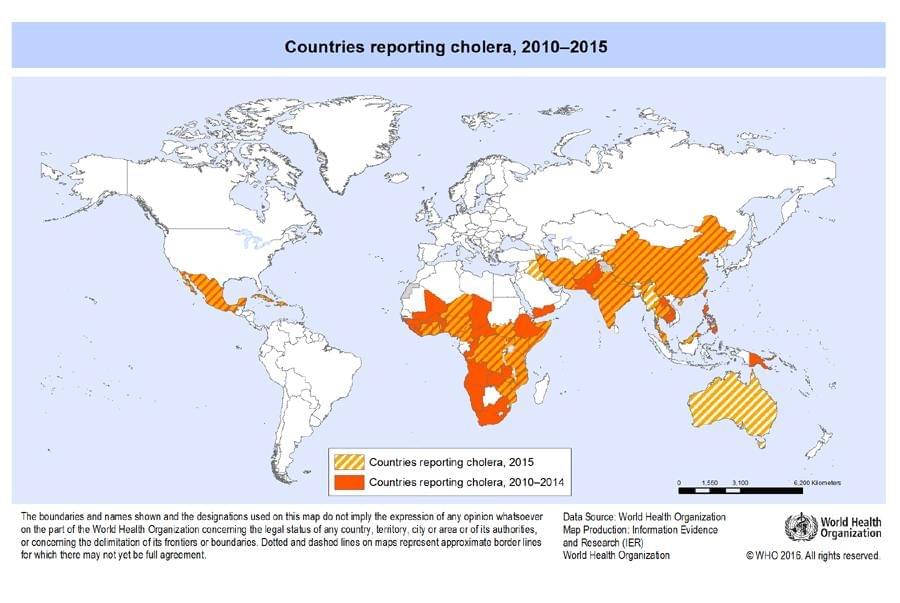

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Cholera remains a global public health threat and is an indicator of inequality and lack of social development. Researchers estimate that there are 1.3 to 4.0 million cases of cholera per year and 21,000 to 143,000 fatalities due to the infection worldwide.

During the 19th century, cholera spread around the world from its original reservoir in the Ganges delta, in India. Seven subsequent pandemics have killed millions of people across every continent. Cholera is now endemic in many countries.

Cholera can be endemic or epidemic. A cholera-endemic area is an area where confirmed cases of cholera have been detected within the past 3 years, with evidence of local transmission (meaning the cases are not imported from elsewhere). A cholera outbreak/epidemic can occur in both endemic countries and countries where cholera does not occur regularly.

In cholera-endemic countries an outbreak may be seasonal or sporadic. In a country where cholera does not occur regularly, an outbreak is defined as when there is at least 1 confirmed case of cholera, with evidence of local transmission in an area where there is usually no cholera.

Cholera transmission is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation. Areas that are typically at risk include peri-urban slums and IDP or refugee camps, where minimum clean water and sanitation requirements are not met.

The number of cholera cases reported to WHO has continued to be high in recent years. In 2017, 227,391 cases were reported by 34 countries, including 5,654 deaths. The discrepancy between these figures and the estimated burden of the disease is due to the fact that many cases go unrecorded due to limitations in surveillance systems.

SYMPTOMS

Cholera is an acute, diarrheal disease, caused by infection of the intestine with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, which is spread by ingestion of contaminated food or water. The disease has an incubation period ranging from 24 to 72 hours, to up to 5 days. The infection is usually mild or asymptomatic, but sometimes it can be severe and potentially life-threatening. About one in ten (5-10%) of infected people have severe cholera, which in the early stages causes:

- large amounts of watery diarrhoea, sometimes described as "rice-water stools”

- vomiting

- accelerated heartbeat

- loss of skin elasticity

- dry mucous membranes

- low blood pressure

- thirst

- muscle cramps;

- restlessness or irritability

The disease causes a broad spectrum of symptoms. 75% of those infected can show no symptoms at all, while more severe cases can be fatal. In its most severe form, the continuous loss of fluids can cause dehydration and shock which, if left untreated, can lead to death.

The large amounts of diarrhoea produced by cholera patients contains a high level of Vibrio cholerae bacteria that can infect other people if ingested, or when the bacteria contaminates food or water, which can lead to further infections.

When treated promptly, infected people can recover quickly and there are usually no long-term sequelae. Once recovered, people with cholera do not become carriers of the disease, but they can be re-infected if exposed to the bacteria again.

DIAGNOSIS

In addition to identification of the symptoms, diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the bacterium in faecal cultures or rectal swabs.

TREATMENT

Treatment of cholera is mainly based on immediate replenishment of fluids and mineral salts. In most cases oral rehydration is successful, but in more severe cases intravenous fluid balancing is necessary (up to 4-6 litres).

The use of antibiotics, such as tetracycline or ciprofloxacin, is recommended, which can reduce the intensity of symptoms.

PREVENTION

A cholera vaccine is available that is a safe and effective weapon against transmission of the bacterium in endemic areas.

In addition, it is always important to protect yourself by following a few simple rules:

- Only drink clean, safe, potable water

- Only drink beverages, like water and fizzy drinks, from sealed bottles

- Use clean, safe, potable water to brush your teeth, wash and prepare food, and make ice cubes

- Clean food preparation areas and kitchen utensils thoroughly with soap and clean, safe water and allow them to dry completely before reuse

- If bottled water is unavailable, bring the water to boil for at least 1 minute

- To treat water with chlorine, use one of the certified chlorine treatment products and follow the instructions carefully

- Wash your hands with soap and clean, safe water:

- Before eating or preparing food

- Before you feed your children

- After using the toilet

- After taking care of someone who is ill

- Use the toilet

- Always use toilets or other sanitation systems, such as chemical toilets, to dispose of faeces

- Always wash your hands with soap and clean, safe water after defecating

- Clean toilets and surfaces contaminated with faeces using a solution of 1 part household bleach and 9 parts water

- Cook safely

- Cook, bring to a boil, then peel

- Avoid raw foods. Always wash and peel fruits and vegetables before eating

- Personal and environmental hygiene

Given the oral-faecal transmission of the bacteria, which often occurs via contaminated food and water, primary prevention of cholera infection involves management and purification of water sources, a functioning sewage system, good hygiene and food safety.

Health education within vulnerable communities on hygienic practices, food preparation and eating habits, such as washing hands with soap and clean water before handling food, is crucial in epidemic control.

Preventing and controlling cholera requires interventions outside the health sector, and also requires engagement with partners in other sectors. The development and implementation of multisectoral cholera control plans is a useful mechanism for bringing together the relevant sectors, opening lines of communication and coordination that will be useful beyond cholera control.