Chagas

Chagas disease, also called American trypanosomiasis, is a chronic human infection caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (T cruzi), which causes heart failure and death in 20-30% of affected individuals. The parasite is typically transmitted by triatomine bugs known as "Kissing Bugs" in the United States, "Barbeiros" in Brazil, and other popular nicknames in the various endemic countries of South America.

Most of the chronically infected people (approximately 8 million) live in Central and South America, where the disease is endemic, but an estimated 300,000 live in the United States, with others in the rest of the world. In South America, disease control and monitoring have been successful in some countries, such as Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, southern Brazil, São Paulo, and Paraguay, but it is seriously lagging behind in Central American countries, such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

CAUSES

Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, a parasitic protozoan that is transmitted by approximately 15 genera of Triatominae. These are insects are from the Reduviidae family, one of main insect families found in several rural and suburban areas of Latin America. They live mainly in mud, thatch and huts, where they hide during the day. They are active at night, when they come out of hiding to feed on blood. This is when they become infected with the parasite, through the blood of infected animals.

T. cruzi has a complex life cycle that involves two hosts, the insect and virtually any vertebrate, and develops in three distinct stages. The infectious stage is called trypomastigote: the parasite has a wavy appearance, with a single flagellum. It is in this form that it passes from the insect to the host. At that point it reaches the cardiac and neuronal cells, where it transitions to the amastigote stage, which is smaller than the other two, oval and flagellum-less. Here it multiplies, until it causes the destruction of the cell. The amastigote then return to the infectious form, or become epimastigote, similar to the first stage but less wavy, which goes back inside the insect’s intestine and multiplies.

TRANSMISSION

Transmission generally occurs when the insect is feeding. However, it is not the bite that transmits the parasite: at these times, as well as feeding on blood, the insect defecates leaving the protozoan behind, where it is then able to enter the host through the bite or other wounds, but also by penetrating the mucous membranes or conjunctiva.

Infection can also occur as a result of transfusion of infected blood, after organ transplants, cells or tissues from infected donors, from mother to child during childbirth and pregnancy, or orally through the consumption of food contaminated with the insect's faeces or the meat of infected animals.

There is no evidence of sexual transmission in humans, although studies have shown that it is possible in other animal species.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

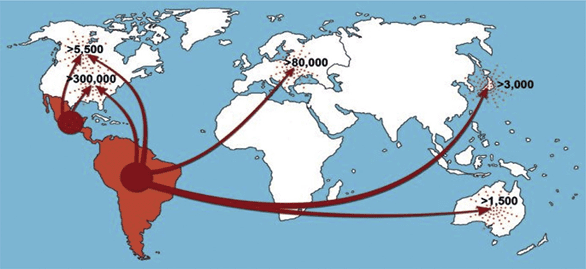

In its chronic form, Chagas disease affects approximately 8-10 million people worldwide, most of whom are in Latin America (where the disease originated). Central America alone accounts for 11 percent of the continent's cases, but as a result of emigrational flows to the rest of the world, there are estimated to be more than 300,000 cases in North America, 80,000 in Europe, 3,000 in East Asia, and 1,500 in Australia.

Control efforts in the southern region of the Americas have shown extremely positive results, with Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay reporting a major decline in the number of cases.

SYMPTOMS

Because clinical T. cruzi infection causes minimal symptoms, it is difficult to diagnose and is very rarely treated, particularly in developing countries.

The incubation period typically lasts about a week. After this period, the disease develops in two key stages: acute and chronic.

In the acute stage, which can last for weeks or months (the average duration is around two months), most people have no symptoms, or only extremely mild symptoms, which tend to resolve on their own. However, it can be fatal in children and immunocompromised individuals, such as:

- Fever;

- Headaches;

- Enlarged lymph nodes;

- Pallidity;

- Muscle aches and pains;

- Difficulty breathing;

- Abdominal pain and chest pain.

At this stage, there is a high presence of parasites in the bloodstream. The trypomastigotes go on to invade the liver, intestines, spleen, lymphatic ganglia, central nervous system, skeletal and cardiac muscles, where they take the form of amastigotes, which causes a local inflammatory reaction.

Because many of the symptoms are generally difficult to identify, the disease often goes undiagnosed. The parasite then enters a chronic phase, in which its presence in the bloodstream is extremely low and almost undetectable.

In most cases, the disease never re-emerges (indeterminate form). However, sometimes, symptoms can reoccur 10 to 20 years after the initial acute infection. 30% of people go on to develop heart problems, which can even result in fatal arrhythmia. Whereas, in 10% of cases there are problems related to the digestive system, particularly the oesophagus and colon.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of Chagas disease is problematic because screening is neither mandatory for the immigration process nor recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Multiple diagnostic, cultural and economic barriers limit the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease. In particular, a University of Texas Chagas disease screening project on the Rio Grande Valley encountered significant technical problems due to the lack of specificity of the available diagnostic tests.

In industrialised countries the diagnostic methods include:

- Light microscopy of blood or tissue smears (in the case of acute stage disease);

- Serological screening test confirmed by a second test;

- Polymerase chain reaction-based tests.

TREATMENT

Treatment of infected infants and children

Cases of congenital T. cruzi infection should be treated as soon as the diagnosis has been confirmed. The current experience of expert clinical groups in treating congenital T. cruzi infection confirms that both benznidazole (BZ) and nifurtimox (NF) can be used to treat congenital cases.

Treatment is highly effective, with fewer adverse events than those described in adults. Treatment success rates, evaluated using conventional serology, are over 90% in infants treated during the first year of age.

Treatment follow-up is recommended using parasitological or molecular testing in the weeks after the infants infected with the parasite have been treated. Once treatment is completed, patients should be followed up every 6 months with quantitative serological testing: the patient is considered cured when the test becomes negative.

Treatment of infected young people or adults

Even in the older populations, patients with T. cruzi should be treated with benznidazole (BZ) or nifurtimox (NF), in accordance with WHO’s standard recommendations.

However, antiparasitic treatment is not advised during pregnancy because the risks of using the available BZ and NF drugs on the foetus are unknown and the risk of adverse reactions is higher in adults. Consequently. infected mothers should be treated after delivery and the lactation period to avoid interrupting breastfeeding following any potential adverse reactions.

PREVENTION

There is no vaccine for Chagas disease, so preventative behavioural measures should be taken to prevent insect bites. The use of insecticides helps, as does avoiding sleeping on straw or mud beds. Always pull beds and furniture away from the wall and check for insects, use insect repellents and bed mosquito nets (preferably sprayed with insecticide).

BibliografyJustin R. Harrison, Sandipan Sarkar, Shahienaz Hampton, Jennifer Riley, Laste Stojanovski, Christer Sahlberg, Pia Appelqvist, Jessey Erath, Vinodhini Mathan, Ana Rodriguez, Marcel Kaiser, Dolores Gonzalez Pacanowska, Kevin D. Read, Nils Gunnar Johansson, and Ian H. Gilbert. Discovery and Optimization of a Compound Series Active against Trypanosoma cruzi, the Causative Agent of Chagas Disease. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, ACS Publications, American Chemical Society.

Luis E. Echeverria, MDa, Carlos A. Morillo, MD, FRCPC, FESC, FHRSb,* American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease). Infect Dis Clin N Am 33 (2019) 119–134. 0891-5520/19/a 2018 Elsevier Inc.

Kevin M. Bonney1, Daniel J. Luthringer2, Stacey A. Kim2, Nisha J. Garg3, David M. Engman. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Chagas Heart Disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019 January 24; 14: 421–447.

Clever Gomesa, Adriana B. Almeidab, Ana C. Rosab, Perla F. Araujob, Antonio R.L. Teixeira

American trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease: Sexual transmission. 1201-9712/© 2019 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of International Society for Infectious Diseases.

Roger M. Mills MD , Chagas Disease. Epidemiology and Barriers to Treat- ment, The American Journal of Medicine (2020)